Fun fact, reader! I wrote this blog post while passively watching Twilight: Breaking Dawn Part I. I remember being really impressed by the CGI used to make Bella look so emaciated by the vampire baby she’s gestating. Eight years later I’m less impressed. Moving on!

Every year, the University of Regina – in an effort to keep with the practices of Open Government – publishes the salaries of all employees making over $100 000. The purpose of making this data public is first and foremost transparency. As salaries are paid with public funds, we have a right to know how and where it’s being spent; especially when those salaries are more than twice the average individual income in Canada. This post is going to draw out the actual significance of this document, and what these numbers tell us about the fiscal action of the University of Regina. There is something to be said for balancing the public’s right to the use of public funds, with an equal right to individual privacy. As such, we will also discuss the instances under which it would not be appropriate to post a person’s salary and the process through which that is determined.

If you’d like to take a look at the actual data in this document, I’ve included a link. What you’ll see in that document is the data as provided by the University of Regina, a spreadsheet of data measurements I completed to give readers and idea of what the numbers as a whole mean, as well as columns checking for errors and measuring growth. The original document lists staff and faculty members by last name, first name. It then shows the salaries received in 2018 and 2019. Some staff and faculty members receive administrative stipends or market supplements in addition to their annual salaries. These are listed in separate columns for 2018 and 2019. Finally, columns showing the total amount received for 2018 and 2019 are listed. In an effort to check for errors, I inserted a column beside the 2018 totals and the 2019 totals. I inserted a function which calculated the 2018 and 2019 totals and did a side by side comparison of the results. I discovered one error in row 201. The individual in this row, did not receive an administrative stipend or a market supplement for 2019. Thus, his total salary should have been the same in the salary column and the total 2019 column but was instead almost $4000 higher. This document accounts for 540 staff and faculty members. One inaccuracy does not give me any pause about the reliability or accuracy of the data.

Another point of interest is the blank cells in the 2018 and 2019 salary columns. Blank cells in the 2018 salary column indicate that those individuals earned more than $100 000 for the first time in 2019. The data shows 73 of these individuals. Blank cells in the 2019 salary column indicate that those individuals received either a reduction in salary from 2018 (thus placing them below the $100 000 threshold) or left the university. The data shows 36 of these individuals. It is difficult to determine the significance of this as there is no indication as to hiring practice, regular salary increase, firing, or natural departure.

Let’s take a look now at the summary statistics I completed to give us an understanding of the data as a whole. I first determined that if $100 000 is the base salary of this list, we need to know the maximum one person is receiving for their work with the University. The MAX function gave us $365 998 in 2018 and $388 025 in 2019. Understandably, the individual receiving this amount is Vianne Timmons, President of the University of Regina. I then completed measures of central tendency to determine the actual representation within this range. I had assumed that these calculations would show that the AVG function would show Vianne’s salary to be an anomaly when compared to the MEDIAN, but the discrepancy was smaller than I anticipated. The AVG salary shows as $135 473 in 2018 and $137 316 in 2018. The MEDIAN salary shows as $130 005 in 2018 and $131 972 in 2019. The AVG salary has a larger growth rate between the two years which might be explained through the 74 staff and faculty members that were added to the list in 2019. I also completed measurements of Standard Deviation and Mean Absolute Deviation. I wasn’t fully sure of the practical difference in these measurements, but my calculations showed a near $10 000 difference between the two. After a little googling, I discovered that the MAD is the more helpful calculation. This determines the average deviation from the average salary when looking at the spread of salaries on a bell scale. This set of data shows the MAD as $22 840 for 2018 and $24 548 in 2019.

These calculations are interesting, to be sure, and might be able to tell us a lot about the University’s staff and faculty spending model in relation to other universities, but unless you’re looking for a specific individual’s salary, the data is missing significant points of information. On the far right of the Data spreadsheet I inserted three ‘Wish List’ columns meant for data that would help derive a greater understanding of the data as a whole. The first column is gender. It would be interesting to be able to examine the spread between men and women receiving a salary of over $100 000. It would also allow for Gender Based Analysis, which is a focus for many institutions at this time. Further to that, my next Wish List column is Department and Title. This would allow, for example, a comparison between Department heads. This, in addition to the gender information, would allow for further Gender Based Analysis. Finally, I ‘wished’ for a column showing the number of years that individual has worked for the University of Regina. If a department head who has been with the University for fifteen years is earning less than a department head who has just arrived, some further evaluation might be necessary. This additional information would increase the value of this document by an estimated (and colloquial) thousand percent.

A few years ago, Teresa Scassa wrote a published an article discussing the merits of public documents, like this one, and the balance of these merits with the right to individual privacy. She explains that the protection of personal data, as a focus of governance, “is aimed at . . . boosting citizen confidence or trust in government so as to enhance public participation” (Scassa, 2014). This is to say that, one way the government ensures trust from the public is by keeping a lock down on our personal information. In response, one could argue that, as a part of democratic governance, public figures who are receiving a paycheck from public funds, are responsible to sacrifice this point of personal information. I’m not going to assert, however, that all of the 540 individuals on this data set, are aware of their public status as a result of their salary. That being said, I don’t think it’s inappropriate for the public to know that 540 of the University’s employees are being well compensated for their work in the difficult field of higher education and higher education administration. It is not my belief that making this information public is a breach of personal privacy according to Scassa’s discussion. This is, however, a subjective matter. The website that holds this posted document notes that the list may be incomplete as it excluded salaries in cases where “disclosure [may] threaten the safety of an individual” (University of Regina, 2019). Scassa addresses this saying that “privacy restrictions on open data may undermine data quality, hampering re-use of the data, or blunting transparency and accountability” (Scassa, 2014). The harm of privacy restrictions could, however, be situational depending on the frequency of implementation and broader impact on the data set. Further, there is the option to keep the data anonymous. The fields could include gender and title – but no department – which would maintain its viability for broader analysis.

Well that’s been a lot about data, openness, and privacy. Beyond whether this specific example deserves more or less privacy, it’s important to remember that almost all government information is public domain. If you have a question about a policy that affects you and how that policy came into existence, it is within your power to find out. And you should! And I hope you do.

Scassa, T. (2014). Privacy and open government. Future Internet, 6(2), 397-413. Link.)

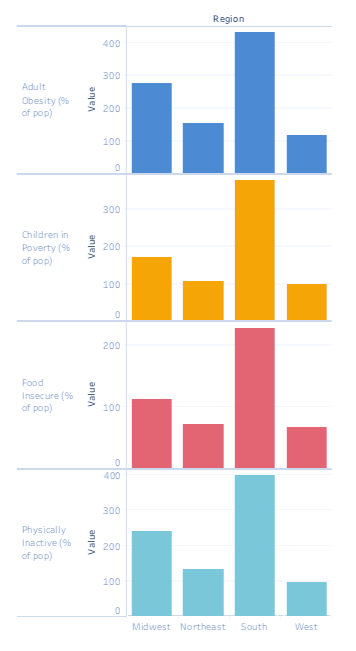

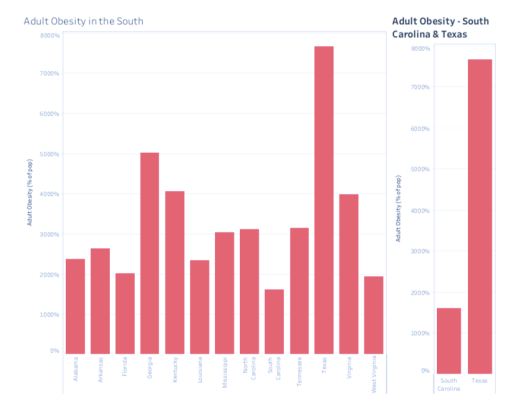

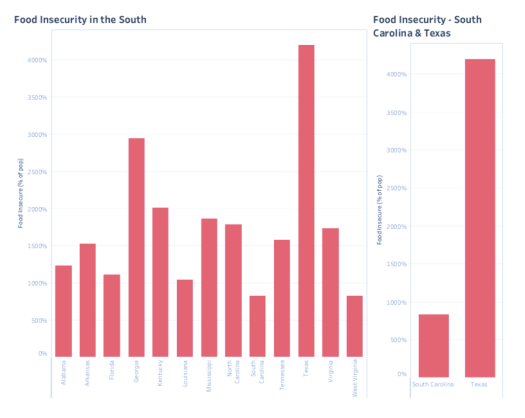

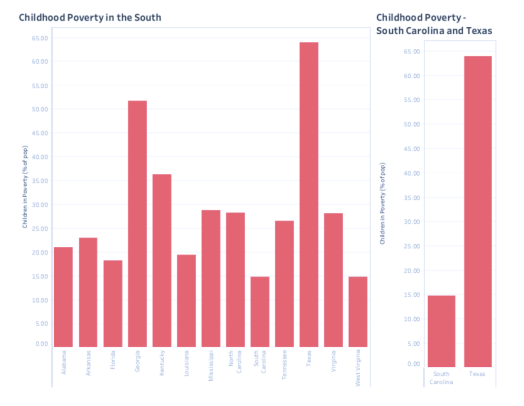

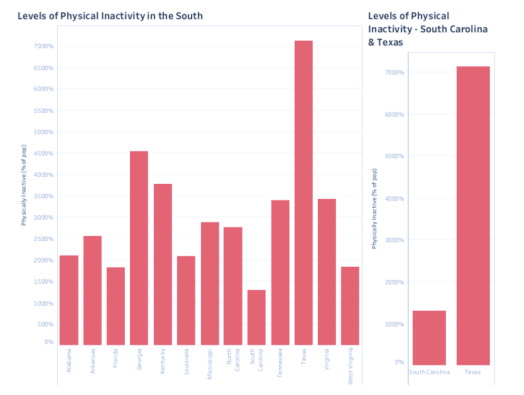

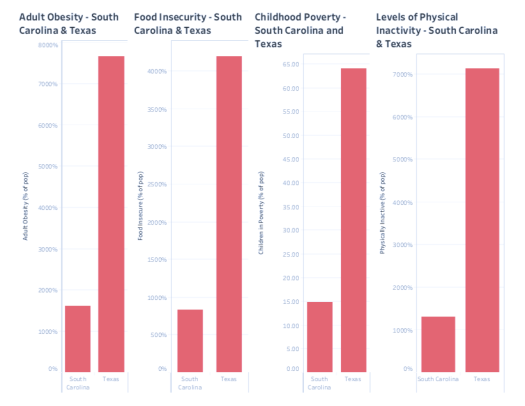

In all four indicators, Texas experiences the highest level and South Carolina experiences the lowest. In the case of Food Insecurity, Texas experiences well over four times what South Carolina does. Margins on the other indicators are no less drastic.

In all four indicators, Texas experiences the highest level and South Carolina experiences the lowest. In the case of Food Insecurity, Texas experiences well over four times what South Carolina does. Margins on the other indicators are no less drastic. This led me to ask the difference between the states. There are the obvious differences. Texas, in land mass, is more than eight times the size of South Carolina and five times the population. Both Texas and South Carolina have coastlines, but South Carolina borders the Atlantic Ocean, while Texas borders the Gulf of Mexico. The economic opportunities stemming from these coasts would be dramatically different. So, controlling for these differences, why does Texas experience such a dramatically different rate of obesity, child poverty, food scarcity, and inactivity?

This led me to ask the difference between the states. There are the obvious differences. Texas, in land mass, is more than eight times the size of South Carolina and five times the population. Both Texas and South Carolina have coastlines, but South Carolina borders the Atlantic Ocean, while Texas borders the Gulf of Mexico. The economic opportunities stemming from these coasts would be dramatically different. So, controlling for these differences, why does Texas experience such a dramatically different rate of obesity, child poverty, food scarcity, and inactivity?

work, and I don’t regret it at all. That being said, I’m glad it’s over and I don’t have to think about it anymore.

work, and I don’t regret it at all. That being said, I’m glad it’s over and I don’t have to think about it anymore.